Talk

Photography as raw material – a conversation about using photography as mass

Participants include Erik Berglin, Tove Kjellmark, Mikaela Steby Stenfalk, and Clement Valla. The conversation is moderated by Kristyna Müller.

In the exhibition Ghost in the Machine, several of the artists work with photography as raw material. The photograph becomes a starting point that is transformed and creates new works; it can be about found images, large quantities of images, or scanner technology that, with information captured through the lens, generates three-dimensional “images.” Many of the exhibited works break with traditional ways of using photography and exploit technical errors, but are also based on fundamental photographic conditions, the connection to reality, and the careful depiction that lens-based media offer.

The conversation is in English and moderated by Kristyna Müller, Director, Center for Photography.

Below is information about the exhibition:

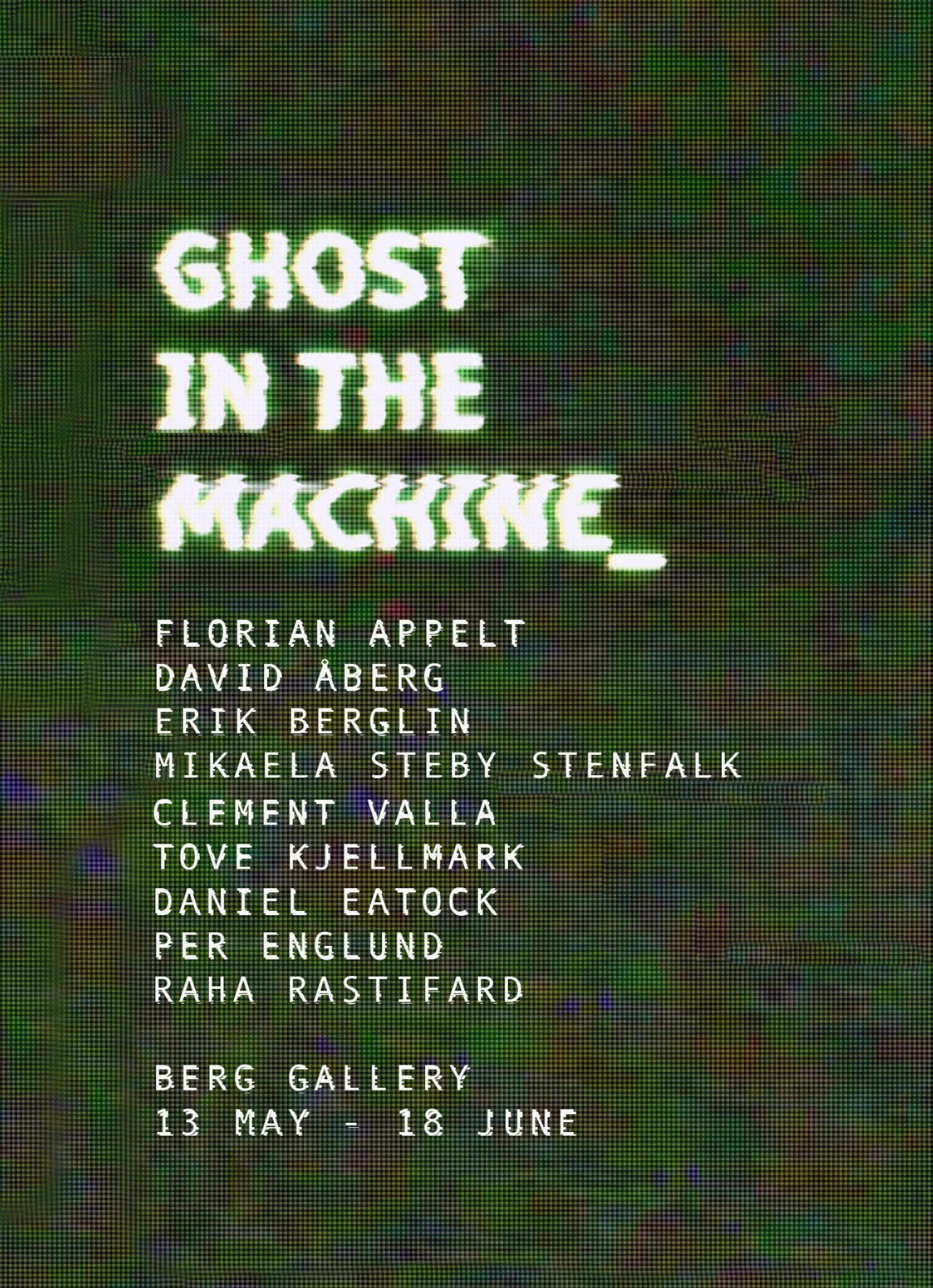

Ghost In The Machine

May 13 – June 17

Erik Berglin / Tove Kjellmark / Mikaela Steby Stenfalk / Clement Valla / Florian Appelt / Per Englund / Raha Rastifard / David Åberg / Daniel Eatock

Can machines think, can they be creative? The question may seem naive, but the recent development of artificial intelligence as a creator of both text and visual material has seriously begun to question the artist’s special position. But instead of seeing technological development as a threat, this exhibition wants to highlight eight artists who work with technology in a curious way, where the mechanical method plays a role as a co-creator of the works. Advanced technology is mixed with analog methods, but in both cases the apparatus becomes a significant factor for the visual result.

For me, thoughts about this began as early as 1997 – when the chess computer Deep Blue defeated the reigning world champion Garry Kasparov. After the loss, Kasparov claimed that Deep Blue must have been controlled by a human. According to Kasparov, the strange and irrational moves that the computer made could only have been performed by a consciousness capable of abstract thinking. Afterwards, there has been speculation that glitches (errors caused by incomplete code) resulted in these random moves. So it may have been mistakes in the software that defeated one of the best chess players of all time! This type of unexpected and uncontrollable glitches is present in several of the works that make up the exhibition.

As in Erik Berglin’s image suite Total_System_Failure which is made by him forcing various image editing programs into situations where they lose control and are forced to generate images or parts of images autonomously.

Tove Kjellmark works with 3D scanning that is translated into vector graphics, which can then be transformed into both sculptures and ink drawings using various machines. The American Clement Valla often starts from landscape images that he appropriates from digital maps. In his acclaimed image suite Postcards from Google Earth, we get a humorous example of what it can look like when a software tries to convert satellite images into 3D environments. Mikaela Steby Stenfalk’s sculpture Copy Collection of Venus de Milo is a paraphrase of Alexandros of Antiochav’s famous sculpture from 150 BC. A software has created a version of the sculpture based on thousands of images uploaded online of the original, but also of images of souvenirs, small soaps and large concrete copies and other things that are supposed to represent Venus de Milo.

The exhibition has borrowed its title from the British philosopher Gilbert Ryle, who believed that the physical body and consciousness are disconnected from each other. Ryle argued that our physical bodies can be regarded as machines that happen to house a spiritual consciousness whose decisions are made independently of how it affects its body. One could say that Ghost In The Machine tries to mirror this reasoning and instead show how machines can make art together with human intervention.

/ Erik Berglin, artist and in this case curator.